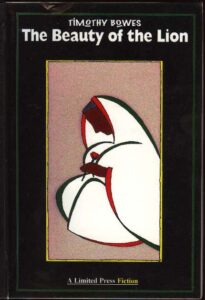

In 1996 I wrote a novel entitled The Beauty of the Lion. From a literary point of view, it was a disaster, but for me as the writer it was remarkably influential.

In 1996 I wrote a novel entitled The Beauty of the Lion. From a literary point of view, it was a disaster, but for me as the writer it was remarkably influential.

There was nothing remarkable about the book itself, except for its particularly sloppy style and poor punctuation. Indeed, I suppose the same story has been recounted a million times before, only with mildly different characters. This was no ground-breaking tale or spectacular innovation; it was, perhaps, just another tired-out rewriting of a quite ordinary life.

Yet as I occupied the lives of those characters for a few short months — mainly in the darkened hours — as I hammered the story into the keyboard and burnt my retinas with the word processor’s midnight glow, a whole new world opened up before me. It is quite true to say that this project started my writing habit, having avoided any kind of hard work throughout my schooling, but this is not what I have in mind. Rather, though completely unintended, my investment in those semi-imagined lives carried me along a path towards an unexpected destination.

The story accompanied two quite unlikely companions: a young Sikh woman from an irreligious family attempting to rediscover her faith and a young white man running away from his. But the story was not about religion, for these faiths were purely markers of identity. For the jumble of atheist, Sikh, Christian and Muslim characters race was the defining identity that caused tensions between them.

So a tale began of how two insecure characters could have become friends were it not for the intervention of their other acquaintances: the Pakistani Muslim girls who befriended the Sikh at school and warned her of the white boy’s crimes, and the boy’s Muslim friends who derided the girl for her odd ways. The Muslim characters were one dimensional, with few redeeming qualities. The girls were judgemental and racist, while the boys befell one misfortune after another.

Naturally, as these tales almost always go, eventually the two saw through the machinations of their advisers and decided to become friends. And so of course the Sikh girl’s brother threatened to break the white boy’s back, and her friends turned their backs on her, and a friendship was exaggerated into something akin to fornication, and though they denied that it was anything more, the girl finally faced the consequences of insinuation and was thrown out of the house and sent away.

And yet that was just the beginning. Fifteen chapters and a hundred thousand words later, a period of fifteen years having passed by in its pages, the novel ended on her son’s first day of school. Her job now ‘was to see that Benjamin-Piara, and Laila, would succeed the way she did, but without the heartbreak and the struggle.’ Apart from the terribly poor writing, it was quite a grim novel — the encounters with racists and criminals were hardly light entertainment — but it had a happy ending, of sorts.

For me, however, that was not the end of it. About four months after completing the project I moved down to London to begin a university degree. A few of my fellow students read copies of my novel, but they were all far too polite to offer any constructive criticism. It did not matter, for I had already come to terms with its flaws. Finding myself in a hugely cosmopolitan environment, interacting with people from all sorts of backgrounds, I was suddenly conscious of the one dimensional nature of the characters in the book and the great complexities of real people. Gradually I was becoming sympathetic to some of the antagonists in my novel and more critical of the two main characters.

As the year wore on and I honed my writing skills penning essays on environmental degradation and theories of economic development, I knew that I had to rewrite that novel. At first I just wanted to improve the quality of the writing, which I knew was poor and immature, but as I committed to revisiting the story it began taking on a life of its own.

The Sikh girl’s friends were not as bad as I had thought. One was just principled in her beliefs. She had her faults like anyone, but her objections to the boy came not from malice, but out of genuine concern for her friend. The Sikh girl was not as certain about beliefs as I had thought: she was just putting out feelers, stumbling to find her way in an environment devoid of guidance. The boy was no pure victim of the vindictiveness of others: he had played an active role in messing up his life.

By the time I returned to my word processor at the start of the summer break and began the novel anew, it was already a different book. Where it had once been clearly about race, now it was threaded with ambivalent questions of faith. Where there was once a certainty about the rightness of some characters and wrongness of others, there was now uncertainty in everyone. The girl that was the thorn in the side of the main players in the first draft had somehow won my respect.

By the time I returned to my word processor at the start of the summer break and began the novel anew, it was already a different book. Where it had once been clearly about race, now it was threaded with ambivalent questions of faith. Where there was once a certainty about the rightness of some characters and wrongness of others, there was now uncertainty in everyone. The girl that was the thorn in the side of the main players in the first draft had somehow won my respect.

In the process of writing a piece of fiction, it was as if the writer had moved a thousand miles. My summer break proved too short and by my return to university to begin my second year of studies I had only completed half of the rewrite, and that was as far as I ever got. My writing had carried me — though not alone, for there were other influences too — towards another world. Before the following summer I would be a treading a new path myself. Not as a well defined, one dimensional creature, but a complicated, ambivalent character that a far greater Creator had willed into existence.

I shall forever be grateful for the pen, for bringing me this far from home. And to the publisher who recognised that the manuscript was best consigned to the bin.

There was an interesting piece on Radio 4’s Open Book yesterday on how a listener who had found it difficult to concentrate on reading since bereavement fifteen years ago could get back into the habit. There is an organisation based in Liverpool which aims to help people like this achieve this very goal and its director, Jane Davis, was on hand with a few recommendations.

Rather than encouraging the listener to delve into a novel, she suggested starting by reading short stories (such as those by Anton Chekhov) and poetry collections (such as the anthology, Poem for the Day, published by Chatto and Windus). Additionally, she suggested listening to a long novel (such as Nikolai Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina) in audio book format.

I appreciate the advice, as I have always struggled with reading. While friends of mine can rattle through several books a week, it takes me months to complete just one. It has always been the case. I clearly remember being sent to a private tutor as a child to fix even the alphabet in my mind, even after at least two years of primary school. I got off to a bad start and I have never really caught up, despite shelves packed with books at home. The stigma attached to illiteracy does not help.

A dear friend of mine is so well read that I am often fearful to confess my ignorance. He will ask me if I have read such and such great work and he frequently speaks with rhythmical fluency that draws on the masters of English literature. I am ashamed to confess that of all the novels I have started reading over the years, very few of them I have actually finished. I am ashamed to confess that my eyes have only scanned over a few pages of each of the books on my shelves.

I borrowed the complete works of Dickens from my father a few years ago in an attempt to enlighten myself, but I managed only a few pages before I returned it to my bookcase to gather dust again. I bought Huckleberry Finn a couple years ago, but only got half way though. I began A Picture of Dorian Gray, but gave up by chapter two. Even a PG Wodehouse eluded me.

There is a kind of book I can manage — the kind that true readers sneer at. I read Salmon Fishing in the Yemen from cover to cover in a couple of days, almost failing to put it down. Indeed, I enjoyed it so much that I picked it up again a year later. Likewise, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Books for simpletons, some might say. But I struggle when it comes to reading.

‘Read! Read in the Name of your Lord who created you!’

I am conscious of these words, for I have seen their effect on friends upon their embrace of this noble deen. I have friends who were once members of gangs, running riot in the streets, who upon adopting Islam as their path have become scholars in their respective fields. A friend once known for pilfering mopeds in his youth is now found buried in history books and impersonating little Dorrit. Another friend who could not even read English before he became Muslim went on to master Arabic. I have seen people who — though barely literate in their former life — have soared to great heights of learning.

I wish I could follow on in their footsteps. I am reading at the moment anNawawi’s Manual of Islam, some eleven and a half years after I was given it. I am making slow progress, but it is a more manageable tome than others. I wish I had discovered it earlier, but I had set it aside when I first received it, for a friend had questioned its authenticity, and it disappeared out of sight, until I rediscovered it the other week whilst searching for another slim work.

The advice on Open Book, then, was perhaps in some ways made for me. Perhaps those pamphlet-like books so mocked by the intellectuals of our community could be my way into a world still somewhat alien to me. And new-fangled audio books could be invaluable too.

But something else too: Liverpool’s Reader Organisation also runs weekly read-aloud groups, in which members of the community come together to read to one another. What a splendid idea. I once attended a gathering where the inner circle passed around a translation of Riyad us Saliheen: each individual read a passage and then passed the book on. It was quite wonderful, I thought at the time. I must sort out something like this of my own.

In her rage at Tony Blair on Friday as he sat before the Chilcot Inquiry she accidentally dashed over a goblet of red wine. To his crimes of forging war and invading a sovereign state, she added the painful stains on the beautiful wooden floor. Thus acts the modern Muslim, scared to take the self to account, always ready to blame another, to upbraid imperialism and the fanatic. The enlightened Muslim seethes at the woman in hijab, the bearded youth and all who embrace a practical faith and eschew the politics of identity, screaming of the intolerable shame they shower upon her. We shall not speak of our abandonment of prayer, of our poison tongues, our short-selling, our aggressive anger. God will not change the condition of the people — recalls the Muslim so chastised, turning back to their faith ever so slightly — until they change the condition of themselves. But the modern Muslim censures everyone but herself. Today, Tony Blair, white imperialism. Yesterday, white liberals, veiled women, Muslim converts. We learn nothing from the upturned goblet.

If you let the rot set in, it will, and it will gradually eat away at all that you have. This is the lesson that keeps on coming back to me. Last night I met a chap whose character shone beauty, as Allah wills. His manners were so appealing that at Isha the only du’a that sprung to mind was, ‘O Allah, give me a character like that.’

For as he sat there — what he did not say ever more telling than what he did — I found myself regretting each cascade of words from my own lips. As he departed, I wondered at my perennial role as court jester. Why could I not just sit in silence, as I once would, and absorb the presence of others? Why now the need to speak so much, and indeed to speak ill, wishing that the vague anonymity might justify such words? The rot has set in, and it is eating away, eating away at my meagre faith.

The more I feed my base desires, I was found reflecting the other day, the more they grow. But this weed doesn’t seem to blossom into its own space, occupying a cavity apart from the rest of one’s life. Instead it seems to thrive like a rampant vine upon one’s core, killing all that falls in its way. And the rot sets in.

Suddenly this ugly vanity. This self-righteousness, despite so much self-wrongness. Suddenly the fault finding. Suddenly the belief that my irksome sins can be ignored. Suddenly this great ignorance, this vast chasm of stupidity. This forgetfulness. This heedlessness.

It takes a character that shines goodness to stir me. All of a sudden I realise how small I am. And how far, far from the nobility I aspired to not all that long ago. A fool sits at his computer, typing.

Often when I get to this point in the year I find myself looking back and reflecting on how quickly the past twelve months have seemed to have passed by. But this year quite the reverse is true: I’m not wondering where all the time went, but pondering how many memories seem to fill the past 300 days. The snow, the passing of a loved one, travels in Arabia, the hard slog in the garden, friends visiting-visiting, the adoption assessments, the family holiday, a month of fasting, visiting friends… It has been a busy year.

Where the garden is concerned, it appears to be a metaphor for my entire life. Keeping it under control and pulling it into shape requires hard work of the highest order. Whenever I neglect it, it is suddenly sprawling out of control until only another bout of hard slog will suffice. It can be a disheartening affair. In late spring the garden was a picture of beauty—and in some ways my heart was in reasonable shape too—but by the end of summer it was a mess once more, and so too was my soul. It could be that hard work on the land is some kind of treatment for my soul.

Transforming a garden path from this…

to this…

was backbreaking work. But it was worth it. In the solitude of the task, I was found conversing within, carrying me far from the lower calls of my self. And at the end of the day, there was no energy left to sin.

I remember the pride when I conquered the vegetable patch, eradicating every weed in the ground…

but alas, weeding is a constant task and within weeks the weeds were once more dominating the plot, my pride long forgotten, as in my heart.

But perhaps there is reason to be optimistic. We conquered that old, rotting out-house…

though sometimes anger was my fuel, not protein.

And though sometimes it seemed like a mountain too vast to climb…

…in time, with patience and perseverance, and hard work, the unconquerable became but a distant memory…

until at last we achieved our goal.

But more to the point was the realisation that the true beauty of the garden is from Allah.

We don’t make the flowers bloom or call upon the butterflies.

We try our best in life, of course, but true beauty comes from above. With this realisation comes immesaurable ease.

I opened The Independent this morning to find a photograph of someone I once knew staring back at me. An entire decade has passed since we last set eyes on one another, but this article by Johann Hari brought memories flooding back. Not because his article resonated with me, mind you, but because his narrative troubled me. In Renouncing Islamism: To the brink and back again, Hari presents that old acquaintance as an ex-Jihadi—or he presents him as presenting himself that way. But the fellow I knew back then was nothing of the sort.

I cannot say I was ever a close associate of his—and so it is quite possible that I missed the portion of the tale that Hari recounts in his article—but we did encounter one another frequently between 1997 and 1999, as we were both students at SOAS in central London.

I first encountered him in the student common room in our halls of residence on Pentonville Road, where he would play pool and chain-smoke cigarettes. He wore designer clothes, had a very fashionable hairstyle and was always cleanly shaven. His rhetoric constantly concerned neo-colonialism, but this never had much impact on me as a student of International Development, where the post-colonial discourse was already commonplace. At SOAS, his assault on the mischief of the West was nothing extraordinary, for the socialists’ arguments were the same.

Even as a non-Muslim I found myself socialising with him quite frequently through my Muslim pool-partner, whom I had met going to a bizarre comedy show at the student union earlier in the year. Our gatherings often took place on Friday evenings in the cafes of Edgware Road, where we would drink bitter black tea and smoke fruit-flavoured tobacco. Again, the talk was of neo-imperialism, of western-proxies ruling the Islamic world and the Khilafah, but memorably the sources were Noam Chomsky, Edward Said and John Pilger.

Those social meetings ceased when I became Muslim in 1998, as I considered the smoking and time-wasting un-Islamic, but I continued to encounter him on campus. I largely kept company with a group of apolitical Salafis at the time, who were fiercely critical of HT whom they considered to hold heretical beliefs. The Salafis believed that the Muslim world would only be reformed by individual Muslims reforming themselves and adhering to the sunnah, whereas HT had a Leninist view that change would come about upon the establishment of the State. Thus I frequently stumbled upon arguments between this fellow and my friends, with the latter mocking HT as the Socialist Worker Party for Muslims.

I am puzzled, therefore, when Hari writes that my acquaintance, ‘wanted to be at the heart of the jihad’, for I never heard him talk about this even once, even theoretically. Instead he was perpetually obsessed with the idea that ‘intellectual argument’ would be the driver for change in the Muslim world. He went on about ‘intellectual arguments’ to such an extent that it became something of a joke amongst the other students.

I have no idea whether the tale of a coup plot involving junior Pakistani army officers is in any way true. However, it is the case that he was involved in an attempted coup in 1999 rather closer to home: not in dusty Karachi, but in the tiny second-floor prayer room at SOAS. Here he intended to wrest control of the Islamic Society from the Iqwanis, who had wrested control from the Salafis earlier in the year.

I know this, because he thought this quite amiable, decent chap would help him. His great talent, as I recall, was not so much in being able to convince people and win them over, but in talking them into submission. He would go on and on at you with circular arguments so that in the end you would agree with him just to be able to change the subject.

And so it was one day when he came over to my flat to argue that something had to be done about the Islamic Society, which he claimed was corrupt and unrepresentative of the Muslim students: he talked at my flatmate and me for ages until we finally agreed to put our names to his vote of no-confidence. Unfortunately he did not get the message when I rang him back to tell him I had changed my mind and the next I knew about it was when members of the Islamic Society came for me, demanding to know why my name was listed on a petition pinned to the notice board in the prayer room.

Alas, I never had the privilege of reading the notice, but was in any case called on to attend a special meeting of the Islamic Society to explain what it was all about, for the instigator had disappeared and was unreachable on his mobile phone. As in Hari’s article, he was never drawn on the details of this coup plot either, but it did make my remaining days at SOAS uncomfortable where the Islamic Society was concerned.

Meanwhile, he continued to organise lectures on campus, inviting academics like Fred Haliday to duels where he would demonstrate the power of his ‘intellectual arguments’. Nobody I knew ever considered him a jihadi, but only something of a friendly bore. Rather than taking him seriously, people dismissed him as a caricature socialist wrapped up in Muslim garb.

Reading Hari’s article, however, he sounds like a great Missionary, steaming off to one Muslim country and then another as if on an adventure inspired by Indiana Jones. Hari writes that he ‘decided to move on to Egypt’. Yet to say that he decided to move on to Egypt is to stretch language a little far. In reality he was undertaking a degree in Arabic at SOAS and was required to spend a year in Alexandria as part of the course, like every other student.

Even there his capacity to talk people into submission was well noted, even by his lecturers, who advised him to reign in his tongue. But he was not one to listen to such advice and was soon arrested for belonging to a banned political party. Upon his release several years later, he appeared on Hard Talk on the BBC News channel, still eloquently and passionately defending HT, once again talking of those ‘intellectual arguments’.

All these memories signal my trouble with Hari’s article. Yes, he was indeed a recruiter for HT and he was dedicated to this cause. But to claim he was a jihadi is to stretch the truth too far. Granted I never attended any of HT’s gatherings to learn what may have lain beyond the mockery of my friends; perhaps, if I had, I might have formed a different picture of him. But in the ordinary interaction between us, and in witnessing his debates with friends and his famous debates with secular academics, I believe I framed a fair picture of the man. He was a passionate and eloquent disputant, absorbed in the kind of post-colonial rhetoric common to many students of the time, like my many socialist acquaintances.

I am not dismissing his devotion to HT or excusing it. I am merely suggesting that the article I read this morning was full of exaggerations. I am not in denial about the threat of extremism within the Muslim community—indeed, I have noted elsewhere the advice I was given to steer clear of known extremists when I first became Muslim. My objection to Hari’s article is that for me it raised more questions than it answered.

Why, I find myself wondering, is it necessary to build oneself up as a great sinner who saw the light—like Paul on the road to Damascus—in order to denounce what is wrong? There are many, many Muslims who have been quietly, modestly, cautiously working on the ground to counter extremism for years and years. Theirs is a thankless task. Condemned by the extremists and ex-extremists alike, their work is ever more difficult. These men and women did not need to venture to the brink and back to realise that it was wrong; they had already delved into their faith and forged a forward path.

Should I be grateful that I saw that face peering back at me from the newspaper this morning, for reminding me of all of this? I’m not sure to be quite honest, but of one thing I’m pretty sure: Johann Hari has just been sent on a wild goose chase. I hope he realises this before he invests too much hope in his new found friends.

The old Pakistani uncle at the mosque is due his seventy excuses too.[1. “If a friend among your friends errs, make seventy excuses for them. If your hearts are unable to do this, then know that the shortcoming is in your own selves.” — Hamdun al-Qassar, narrated by Imam Bayhaqi in his Shu`ab al-Iman 7.522.] People like me are often found muttering taciturn complaints about the unfriendliness we perceive in our fellow travellers when we come together for prayer. In weeks and weeks it could be as if we are not even there, as if ghosts standing in line.

But to give your brother seventy excuses was the lesson I learned when I returned to the mosque after some months’ absence. There was a time—when I was doing better—that saw me hurry there for every prayer, until laziness got the better of me. My Lord would note my disappearance, I told myself, but no one else would miss me.

I was wrong. As I wandered into the mosque that afternoon, an old, white-haired man with weak English got up from his place and headed straight for me. ‘Where on earth have you been?’ he asked me, ‘We thought you’d fallen dead.’

A minute later another approached to ask after me. Had I been away? Had I been ill? Um, no, I muttered, I’ve just… ‘Well as long as you’re alive and well,’ he interjected, sensing my inability to account for the months that had passed.

It is difficult to prise many words from these old folk. Salam alaikum is usually all they will spare, or the occasional, ‘How are you brother?’ We don’t have conversations, but that afternoon encounter taught me much. Perhaps they’re shy. Perhaps English isn’t their strong point. Perhaps they’re waiting for me to strike up the discussion. Perhaps their mind is on the prayer. Perhaps they have problems at home on their mind. And for the literalist, this is only seven percent of the excuses due to them.

Nowadays I attend the midday prayer each working day in another town. The folk there don’t seem all that friendly either, but here I have learnt to give them their seventy excuses too. We may not sit and chat when we come together for prayer, but still we are brothers to one another, witnessed in random acts of kindness.

My office lies a fifteen minute walk from the mosque—a hurried march there beside main roads set apart from my leisurely saunter back along the cobbled streets of the old town. It is in this daily journey that I learned my lesson, for I have lost count of the number of times someone has stopped to give me a lift. Often I don’t even recognise them as they come to a halt beside me, tooting their horn, but it doesn’t seem to matter. ‘Salam alaikum,’ they say as I peer in at them, ‘Do you want a lift?’ Or, ‘You’re going to miss the jamat. Jump in.’

Most of the time we don’t strike up conversation. We exchange salams and I reiterate my gratitude, but that’s it. But it does not matter. These random acts of kindness serve to remind me that things are not always as they seem. When someone is silent it doesn’t necessarily mean that they don’t like you; they may just have nothing to say.

Sometimes I am too hard on people, jumping to conclusions and making assumptions about them. And sometimes I fail to give credit where it’s due. Bumping into a couple of friends from Arab lands after Friday prayer one week, conversation soon turned on our favourite bugbear: the incomprehensible Urdu speech followed by the hastily sung generic Arabic sermon. It’s a problem, I had to agree, but then another thought occurred to me. ‘Of course,’ I said, ‘were it not for these people, we wouldn’t have a place to pray at all.’

Beside me, my friend stopped and smiled. ‘That’s very true,’ he said, and soon we were considering our own shortcomings. And there were many.

Why all the killing? I really cannot comprehend it at all. A bomb planted in a Peshawar marketplace extinguishes the lives of 91 in an instant as it rips through everything in its path; 200 more are left injured. Just a matter of hours earlier 150 are slaughtered in Baghdad.

Islam holds that indiscriminate violence is makruh (offensive) on the battlefield and haram (forbidden) in a place where there are civilians. This slaughter follows not the sunnah of our Prophet, upon whom be peace, but that of the twentieth century, during which 250 million people were needlessly killed. Fifteen million during the First World War, 9 million during the Russian Civil War, 20 million under Stalin’s regime, 55 million during the Second World War, 2.5 million during the Chinese Civil War, and on, and on.

Who gave Muslims permission to adopt the sunnah of the Luftwaffe and RAF, who once championed terror bombing for utilitarian ends? And who gave them permission to abandon the sunnah of the Messenger, peace be upon him, which forbade attacks on non-combattants?

Who now will stand up to the killers and defend our deen and the common man? If a man in the midst of this anarchy must now blunt his sword and resign himself to a fate like that of the better of the two sons of Adam, does the burden then pass to those of us living in safety and security?

For years Muslims have lamented that though we condemn terrorism repeatedly, nobody hears us. But today we realise that all this time we have been addressing the wrong ears. Those who needed to hear us were not our angry neighbours, but those men wielding high explosives and an alien utilitarian way.

Amidst the carnage of a bombed-out marketplace, who now will make themselves heard?

Some of my friends are angry with me, dispatching lengthy emails voicing their dissatisfaction. I know I should be hurt and offended, but instead I find myself thinking that this is just the voice of the Divine, revealing itself through His creation. I could compose great tracts in my defence, but I fear it would be futile. My friends, no doubt, have legitimate gripes, but it is the anger of my Lord that concerns me. Yes, I have been a fool of late, hurtling off once more towards oblivion, and my Lord witnesses all things. Is anger not His right? The friend rails against what they see—or what they think they see—but with the Lord of all the Worlds feeble petitions such as mine carry no weight, for He knows both the inner and the outer, the hidden and the seen. How much better to be called to account by friends, causing a moment’s discomfort and then reform, than to awake on a Mighty Day to witness one’s utter downfall? With the last of the epistles comes not a rush to pen excuses, but instead to return to my Lord, prostrate. Alas, the call to foolish things is strong, pulling hard from within. But in the fallible words that call me to account are the echoes of my state. So slowly comes the acceptance that there is only one path for me. Struggle, I tell myself reluctantly; struggle in His Way.

There is a disease that I have harboured for the best part of my life. It accompanied me as a child, an adolescent and an adult; as a Christian, an atheist, an agnostic and a Muslim; and in times of both health and sickness. I would define it as a disease of the soul — a spiritual malady — that stifles realisation of any lofty goals. As familiar symptoms return as the years pass by, it becomes ever more apparent that it is an addiction. I turn to treat it frequently and promise to abstain, but in time the cravings become too intense, sometimes manifesting themselves in physical form, and once more I succumb.

In my mind’s eye, I can map out every resolution of reform, for I have long recognised the nature of this disease, striving to conquer it whenever the moment of clarity descends. There was that cold night on Christmas Eve — perhaps 1990 — sitting alone in my bedroom, my parents at church for the midnight service, the window obscured by condensation; I sat on my bed with my bible between my palms, conversing inwardly on the sudden urge to seek out righteousness in place of this affliction. I resolved to displace the ailment with faith and determined to focus on the bible now, reading it from cover to cover, penning my own copy in the process. What happened thereafter, I do not recall, but it is most likely that I forgot my pledge as the sun rose on Christmas morning and the celebrations carried us away.

Another resolution came in my second year of university. The virus was becoming epidemic, infecting every private moment, calling me towards ever lower depths and pulling me closer and closer to despair. My conversation with this agnostic’s God became hopeless, giving in to a grim fate after a death that somehow felt so close. Then one morning I arose and took to the streets of London in a crisp, cool sunlight, the sky an enlivening blue. My steps were aimless, but I ended up in the Regent’s Park, cutting through its beautiful gardens with my mind a million miles away from there, until all of a sudden I was very much there and abruptly conscious of myself. In that instant came a prayer: a resolution of instant reform and dedication to my Lord. In the days that followed I made contact with evangelists and took up their invitations of months before.

Such resolutions — and my revulsion for myself — became key drivers of my search for God and faith. It felt over those first days and weeks after my testimony of faith, months after that Saturday sojourn, as if a great burden had lifted. With belief in God and His messenger came a desire to be good now. The weather was hot and dusty in the city that summer, yet it was in my mind that I felt my sins burning up and blowing away in the wind like parched dust. I had broken the chains, I naively thought, as I adjusted myself to my new-found faith.

This disease, however, is pervasive and deeply ingrained. I frequently blame the television of childhood and the gaze of my infant eyes for planting the seed that has grown and grown, until it has become more rampant than the Russian Vine in my garden, or like the Bamboo the previous owners foolishly thought fit to plant. The kernel of this ill may have been miniscule, but the years have fed and nurtured it, creating a monster whose shoots push up from a new fragment of root whenever another is cut off and cured.

Another marker on the map comes to mind as if it were only yesterday. It had not taken a year for this soul to relapse into the ways of old — in fact it may have only taken a matter of weeks — and soon the self would justify its conduct, normalising it and dismissing the significance of such minor matters. But in time this would dissatisfy me, for I could not promise that the minor would not become major and undermine whatever I had achieved. It was a realisation that struck me one late spring day in 1999.

I had finished my studies for the day and was heading back to my flat beside Waterloo Bridge on the southern bank of the Thames. My saunter, as always, had carried me along the western edge of Russell Square, along Montague Street, half-way up Great Russell Street and down Museum Street. Now I was meandering up Drury Lane. Half way along my portion of the street I sidestepped Jay Kay from Jamiroquai as he got out of his Lamborghini[1. Fame had clearly aborted the environmental message of his early lyrics.], but inner thoughts prevented me from glancing back or lusting for his Italian marque. I was mulling over reform: the time had come, I was telling myself, to finally conquer that disease. A voice was asking questions: will you really abandon all of that, when your life is so long and you so weak? But my mind was suddenly conscious of the Hour and mindful of punishment if nothing changed, and convinced that death could come at any minute. As I cut onto Bow Street I arrived at a reluctant retort. Yes, I would abandon my addiction and dedicate myself to God and His way.

Why I remember that conversation as if it were yesterday, I do not know, except that it was a pledge that I failed to keep. Weeks would pass — perhaps even months —when I would persevere patiently, ignoring the call of the ogre within, but eventually I would succumb to it. How many times I have resolved to reform and overcome this great infection, I cannot say or count. Another conversation came one hot afternoon on my return from Friday Prayer on an early summer’s day in Ealing. Another came on a painfully frosty night in mid-winter as I awaited a train to carry me home.

I oscillate continuously between a call to righteousness and the call of a pervasive addiction that never seems to leave me, regardless of good intentions or the sincerest resolve to leave it behind. It is what evangelists refer to as ‘the addictive grip of sin’ and what Muslims call ‘the domineering nafs’. I call it my great test, and it is a test I would not wish on anyone.

The past two or three years, I fear, have been worse than those earlier years. My memory fails me, of course, for in the continuum of life it is the same old-same old. But worse because I now know better: because a teacher has taken time to explain the stages of the nafs and provided the tools to overcome such burdens, because I have awoken to the necessities of faith, because I am supposed to be older and wiser now. My faith provides the resources to climb to a great height, but there is no instant panacea for any ill; we are required to exert effort, to persevere and be strong — as in any field of life — or else we fail.

Earlier this year I believed that I had cured my addiction. Months passed when its symptoms ceased, when I preoccupied myself with other tasks in order to dull its calls, when I shut down each avenue that would lead to this giant’s reawakening. Imagine if I had succeeded! In my mind it is like a golden ticket — if only I could grasp it, I tell myself, I could then progress. What a blessing to be close to one’s Lord! What a blessing to earn His pleasure! What a blessing to rise in rank before Him! But alas!

I must have compromised somehow — opened the door a crack — for all my achievements of the early part of the year have now been lost and reduced to just a distant memory. Could I not just repent and start over? If I have achieved forty days once, can I not again? If I have achieved sixty, why not try to better it, and gradually — pole pole ndio mwendo[2. A Swahili proverb that roughly translates as, “Slowly, slowly fills up the bowl”.]— build up some kind of immunity? I should aspire to that, at least, I know, but with each resolve to return to God my determination weakens. Mankind will never comprehend the mercy of God; when we despair of His mercy, it is really despair of ourselves, for though our Lord can forgive a world’s weight of sin and more, man is short on tolerance. Yet in truth it is not disbelief in God’s mercy at all, but rather surrender to addiction.

Two weeks ago came that resolve to turn to righteousness and abandon foolish ways. I knelt in prayer and tried my best to eradicate every trace of the poison that had welled up like a bitter sore. But soon the cynic within was once more whispering those familiar counter-arguments, chiselling open the crack, nudging the door back open. And so, so soon, the foolish ways returned, each period of reform narrowing against the last, until it is but a slither of time: the proverbial mustard seed, perhaps. Last night, again I resolved to change, to strive in His way. But by morning I could hear the virus calling.

And now? What now? My sorrow stems from my acute awareness of the affliction. Were I an ignorant fool succumbing amidst blindness to the realities around me, surely I would find respite. But instead I am a learned fool: one that knows of right and wrong, good and bad, of the diseases and cures of the heart. For such a fool, what hope could there possibly be, except the undeserved mercy of His Lord?

All of this, my dear friends, is the woeful curse of addiction, the oscillation of the wayward soul. So don’t be a fool like me, my friends. Shelter yourself and your children from the poisons of this world, and seek refuge in your Lord.

Recent months have seen a sudden upsurge in devotion to the Christian faith amongst followers of the British National Party (BNP) and the English Defence League (EDL). In June the BNP chimed against the Islamic colonisation of Britain, seen in the widespread conversion of churches throughout the land: the Central Mosque of Brent; the former Forest Gate Church; Peckham’s St Mark’s Cathedral; West Didsbury’s Albert Park Methodist Chapel; Oldham’s Glodwick Baptist Church; and 250 year old Brick Lane Church in London’s Spitalfields (once a French Protestant church, a Methodist chapel, a synagogue and now a Bengali mosque). All of these churches — and many more — have fallen to the Islamic invasion.

The BNP are not alone. As the EDL prepare to descend on Manchester on 10 October to protest against Islamic extremism, a video has appeared on the internet, making a rallying cry for England’s Christian heritage.[1. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWcGOt4btwY (spiritofstgeorge)] In his video entitled, ‘EDL: Defending our heritage & birthright – Manchester Oct 10th 2009’, Lionheart of Luton, Paul Ray, builds a picture of a nation under siege. While it begins with headlines captured from the Daily Mail and the Express to illustrate how Muslims receive special treatment — whilst England’s natives suffer at their hands — this is another ode to the churches of England.

‘Manchester England,’ reads a slide midway through the video, ‘The destruction and desecration of a Christian Church and graveyard to make way for a Mosque’. The slides intersect a video showing a tracked Komatsu digger moving earth within the grounds of Longsight’s St John’s Church. The next slide reads:

Are yesterday’s politically correct Church leaders irrelevant to us in todays United Kingdom? Psalm 81:9 There shall be no foreign god among you; Nor shall you worship any foreign god.

In this video, the EDL has messianic pretensions, likening church leaders to the corrupt Pharisees of old, but they would rather not share the Christian message here. Instead, invoking the book of Samuel, they turn to an earlier saviour for inspiration. The EDL is David to the Muslim Goliath in England’s midst:

The Saul generation of Church leaders is coming to an end with the emerging David’s poised to take their place. Please show God where you stand and pray for the United Defence Leagues and their members

The video from St John’s is followed by newspaper clippings about the resignation of Bishop of Rochester, Michael Nazir-Ali — the only bishop, we are told, who grasped the extent of the threat of Islam to British civil society. Nobody mentions Kenneth Cragg these days, while the intellectually brilliant Rowan Williams is dismissed as some sort of loony. And so it is left to the EDL to defend Christianity, not just from the Muslims, but also from parish priests, pastors and impotent Bishops:

The David generation leaders are already in place and speaking the truth on-behalf of His people

Are you one of them who is willing to stand against the Islamification of this Christian land?

A little probing reveals that the source of the video showing building contractors working on the church site is a BNP supporter, who posts the full version on YouTube entitled, ‘Saint Johns, Christian Graves Desecration’[2. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Z6o5Ccwb0A (SuperAceofDiamonds) ] with the description, ‘Graves desecrated at Saint Johns Church in Longsight, Manchester, England as Church is converted into Mosque.’ The BNP itself has an article featuring both the video and further photographs on its website.

There is a problem, however. When I researched the history of St John’s, Longsight, I found that it was decommissioned in 1999. Neighbouring St Agnes — ‘in this place will I give peace,’ inscribed above its entrance — now houses the abandoned church’s statue of St John the Evangelist in its nave. It has taken the BNP and EDL an entire decade to lament the loss of this historic place of worship and its descent into disrepair.

Of course, the key issue riling the nationalists is the desecration of the site. But here again there is a problem. A quick enquiry with the City Council reveals that St John’s Church is a Grade II listed building, which means that it is considered nationally important and of special interest.[3. Listed buildings in Manchester by street, Manchester City Council — http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/514/listed_buildings_register/1908/a-z_of_listed_buildings_in_manchester/18 ] To make any changes to such a building requires the owner to apply for building consent.

Lo and behold, we discover that planning permission for a 16 space car park in the church garden was granted early in 2007. In the intervening period, the owners have spent £50,000 repairing the building, which now houses Dar-ul-Ulum Qadria Jilania mosque and Islamic Centre. A photograph on the BNP website clearly shows that the graveyard has been carefully preserved, although the picture has been tagged, ‘grave-in-front-OF-DIGGER’, since the work in the church garden can be seen in the background.

It turns out that the graveyard has not been touched at all. But if it had been, should we not expect the BNP and EDL to be enraged whenever a graveyard comes under the developer’s gaze? Locals certainly protested when a builder obtained planning permission to redevelop a derelict chapel in Coedpoeth, Wrexham, which included plans to build luxury flats and a car park on top of approximately 100 graves in 2007. But as far as I can tell, the BNP did not join their protests.

The truth is, the redevelopment of graveyards is a fairly common occurrence in the United Kingdom. Rehoboth Baptist Church in Horsham, for example, has just completed construction of a seven space car park and garden of remembrance on its former graveyard. Planning permission to remove the headstones without disturbing the actual graves and to block pave part of the site was granted in 2005. The BNP and EDL, of course, will not be protesting about this car park on this graveyard.

And that’s the problem. The BNP and EDL wish to use the redevelopment of church buildings as ammunition against Britain’s Muslim population, but the facts do not support them. Reading their literature, you would imagine that hoards of Muslims were running amok throughout the land, confiscating church property at the expense of lively congregations. Nowhere is the reason for church closures mentioned — ironically for people that speak of a David Generation, a term commonly employed by those concerned with conquering the personal Goliaths of the ego, there is no introspection here.

Nor are the numbers of closures put in context. For while seventeen hundred Anglican churches have been made redundant since 1969, there are still over 48,500 churches of different denominations serving their communities nationwide. Moreover, over the same period, The Church of England opened more than 500 new churches, while continuing to maintain over 16,000 others. If, as some claim, there are now seventeen hundred mosques in the United Kingdom, this is still only 3.5% of the total number of churches in the country (interestingly the Muslim population of the UK is a similar proportion of the whole).

If Muslim worship appears to be more visible than that of the Christian, it could only be because the Muslim still views the Friday Prayer as England’s Christians viewed Sunday Worship one hundred years ago. Even a believer on the borders of his faith still feels duty bound to put on his Friday-best once a week. But it would be misleading to suggest that seventeen hundred mosques have sprung up in place of the seventeen hundred Church of England buildings closed over the past forty years, for Anglican churches have covenants conferred upon them which usually prevent them from being used by other faith communities. While BNP leader, Nick Griffin, has claimed that Church of England buildings are being turned into mosques, ‘up and down the country,’ it is actually rather hard to find any. The closest I can find are a couple of gurdwaras utilised by the Sikh community.

If my own experience reflects a wider trend, I would suggest that only a handful of mosques in Britain are of great note. Converted houses, rooms above shops, disused warehouses and hired halls in multi-cultural centres are all included in the number of mosques in Britain. The Archbishop’s cubbyhole under the stairs for private prayer would not seem out of place in our sometimes ramshackle collection of prayer halls. Nevertheless, it is true that Muslims have bought former churches — notably redundant Methodist chapels which seem to be in great supply.

So the BNP and EDL have a point? Well I don’t think so. While ranting about St John’s, Longsight, they completely ignore St George’s, Hulme, a Grade II listed building built in 1823 which has been converted into a place of residence, a mere two and a half miles away. But why should this surprise us when they also ignore the conversion of former churches into restaurants, gyms, pubs, nightclubs, shops and private apartments? Brixton’s St Matthew’s church is now the Mass nightclub, which promises revellers loud music, all night dance and expensive spirits. O’Neill’s on Muswell Hill Broadway, housed in a grand old church, offers cheap food and Guns ‘n’ Roses. Cheltenham’s St James’ is now an Italian restaurant. St Luke’s in Heywood, Lancashire, located 14 miles from Manchester City centre, has been turned into a huge family home, featuring six double bedrooms. And for between £250,000 and £500,000 you too can own one with estate agents listing hundreds of former chapels, rectories and churches, already converted or waiting to be converted, with planning consent already obtained.

If the BNP and EDL were genuinely concerned about the loss of historic places of worship and the demise of their Christian heritage, they would say to their members, ‘Look, churches are closing all around us because we don’t use them. We need to start making Sunday special again.’ That task, however, would entail asking their followers to take personal responsibility for their lives: that only ten percent of British Christians regularly attend church cannot be blamed on the mainstream political parties, on multi-culturalism or political correctness. It certainly can’t be blamed on the Muslims.

But the likely response of such people would be to say, ‘Don’t bring religion into this.’ Though they claim to be defenders of the faith, they are in fact like the utilitarian jihadis who dispense with the boundaries of religion, claiming that the end will justify the means. Like those who ignore the prohibitions of their faith, the BNP and EDL ignore the message at the heart of the religion they claim to hold dear. When Jesus — peace be upon him — was asked which were the greatest commandments, Christians believe that he replied:

“The first commandment is this: Hear, O Israel; The Lord our God is the only Lord. Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength. The second is this: Love your neighbour as yourself. There is no other commandment greater than these.”[4. Gospel of Mark 12:29-31]

If this message is unclear to those of the David Generation, Jesus — peace be upon him — is reported to go on to say, ‘But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.’[5. Gospel of Matthew 5:44] And if they insist on bringing, ‘I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword,’[6. Gospel of Matthew 10:34] let them read it in context: Jesus — peace be upon him — knew that most of his people would reject his teachings, which would divide both families and communities. His was a vision of a just society: he overturned the tables of the moneylenders in the temple, he promoted fair treatment of the poor and forgave his enemies. In the context of his time, many of the parables appear as much an assault on the social injustices of his society as messages for spiritual growth.[7. See for example Jesus the Prophet: His Vision of the Kingdom on Earth by R David Kaylor, John Knox Press, 1994]

More famously, perhaps, we have the Beatitudes: blessed are the are the poor, the hungry, the weeping, the hated, the meek, the merciful, those pure in heart, and the peacemakers.[8. Gospel of Luke 6:20-23 and of Matthew 5:1-14] A worthy message indeed, but one clearly lost on those self-declared champions of Christianity in Britain, the BNP and EDL.

Last Thursday, twenty Muslim gravestones were pushed over and a number were broken at Manchester’s Southern Cemetery on Barlow Moor Road.[9. Manchester Evening News, 2 October 2009 — http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/1153293_muslim_graves_targeted_in_hate_attack ] It is not possible to say at this stage who was responsible and what motivated them, but the Police are treating it as a racially-motivated crime. It is not inconceivable that it was a revenge attack for the alleged desecration of Christian graves at St John’s, Longsight — a mere ten minute, four mile drive away.

Love your neighbour as yourself? Love your enemy as yourself? Blessed be the peacemakers? I will leave you to draw your own conclusions about the authenticity of the nationalists’ new found faith, and where it is liable to lead us.

I have long been one of those admirers of the Muslim woman, who says, ‘How I wish I had faith the strength of theirs.’ For to take upon a visual marker of identity outside the norms of society and to wear it whenever one wanders into the public eye takes great courage. Observing English women wrapping their heads in fabric soon after embracing the deen, I used to wonder at their faith. Had I been born on that side of the gender divide, I would ask myself, would I have had the daring to envelop myself in that unfamiliar garb?

The mirror, however, has been speaking to me these past few days and it has reminded me of the shortcomings of my biased admiration. The act of revealing one’s beliefs through the physical is not confined to Muslim women alone. For the Muslim man, the clearest marker is his beard. It is true, of course, that a beard does not automatically identify one as a Muslim, whereas the hijab, except amongst the unenlightened,[1. My wife has been mistaken for a nun on several occasions — white skin, you see.] almost always does.

I believe it takes great courage to wear a headscarf — not to mention persistence, tolerance and fortitude. I have often heard it said that some women find wearing the hijab saves time getting ready to go out, but I can’t think how this could possibly be true, for it takes me at least ten minutes and numerous pricks to my fingertips to close a safety-pin if I can’t see it — and you don’t have to iron your hair.[2. Although I have glanced in the mirror half-way through a working day and realised that I still have punk tufts all over my scalp too many times to count.] Of course it may well be true in the case of the Afghan veil or Somali khimar, but I am hugely doubtful that sartorial convenience is utmost in the minds of those who choose to cover.

You must have a certain determination and spiritual height, I am often found reflecting, to move amongst people who are commonly contemptuous of your faith, announcing by your appearance that you are a Muslim. Although only Allah knows what our hearts contain, to me it signifies a level of iman worthy of respect.

Yet the mirror speaks: at least the act of putting on a headscarf is within the woman’s control. So long as a woman has enough money to buy a metre of fabric, she can consider herself a hijabi. Her male counterpart, however, is at the mercy of his biology. While she decides whether it will be a pashmina or a khimar, and black or blue, or floral, and cotton, wool or nylon, he stands there wondering if it will become a thick Afghan mane or a straggly Malaysian outcrop, or if it will forever remain a single whisker dangling on the end of his chin.

Adopting the hijab can be a slow process, involving a readjustment of one’s mindset — and that of one’s friends — sometimes stepping from bandanna to scarf and back again. Yet once a decision to wear a headscarf has been made, the transformation is immediate. A scarf does not grow in patches. By contrast, for some of us, the road towards achieving anything even resembling a beard can be a long one, complete with the accompanying chastisement and mockery favoured by those around us.

Pious Muslims — both men and women — like to remind the fresh-faced ones of their grave shortcomings. I decided to grow a beard when I became Muslim in 1998, believing it to be obligatory, but over the years that followed others would pick up on my lack of facial hair and find my faith wanting. Attending a series of lectures, three months after I became Muslim, somebody twice asked the speaker if growing a beard was fard. Each time the respected teacher answered the question with the affirmative, he looked directly at me. My three whiskers were inadequate there, but still I persevered. My family and friends did not need to sit staring at my chin as we conversed, for I knew that I looked peculiar, but for the next few years they always would, whenever we met, without fail. I would console myself, imagining an angel swinging beneath my chin as in a hadith I had once heard.

As the years passed by, my whiskers gradually multiplied, resembling a tray of salad cress as they grew longer. With them came more mockery. ‘What’s with his chin?’ a consultant would ask a colleague, who insisted on calling me d’Artagnan. ‘He’s a Muslim,’ she would reply with raised eyebrows, sniggering something about my three musketeers. Now they call me Oliver Cromwell and Shakespeare at work. Cryptically they ask me how the novel’s coming along before guffawing, ‘Shakespeare!’ yet again — I don’t have the heart to tell them that he was a playwright, not a novelist. It amuses me, somehow.

The mirror has been reminding me of all this since the end of Ramadan. For the first time in my life, something resembling a beard has begun to populate my face, sparse though it remains to the casual observer. I am fortunate to discover that medicines sometimes have beneficial side effects. Though the pious ones still turn away, dismissing my corruption of the sunnah, for me it is a start. Some are unable to comprehend that it could take eleven years to grow a beard, or that one could fail to grow one at all.

Though I have long been an admirer of the Muslim woman’s faith, the mirror proposes that the Muslim man’s faith is no less meagre. The visual marker that he takes on may not provide that instant flash of identity recognition, setting him at odds with the people around him. But somewhere in the process — whisker to goatee to garibaldi — as a mass of evidence amounts that it is not worth the trouble, it becomes self-evident that we persevere for a reason. The Muslim woman does not wear her headscarf to avoid brushing her hair in the morning. The Muslim man does not grow a beard because it saves money on razors. We persevere, in the face of criticism and mockery, because we want to please our Lord. It is only one aspect of our faith — and it is our hearts and our deeds that concern our Lord — but it is still a start.

Dear Editors,

Explain to me, would you, what this means: ‘Sebastian Faulks outburst risks anger of Muslims’? Or this: ‘Sebastian Faulks has risked sparking Muslim outrage…’

Does it mean that you have not yet found any angry Muslims and you’re stirring? Or is it just that you’ve taken your risk assessment training a tad too seriously?

‘The bestselling author Sebastian Faulks has courted controversy by saying the Koran has “no ethical dimension”.’

He has courted controversy, has he? And how is his courtship going? Are Muslims engaging, or as it seems to me, are they too preoccupied with a month of fasting and prayer to lap up this manufactured schism? The comment fields are filling up with condemnation of backward Muslims who have no respect for free speech, for sure, but the Muslim voice is strangely absent. Hence ‘risk’.

As for you, Mr Mair, what was with that package on PM last night? No, don’t get me wrong, it was quite fascinating and instructive. I was just wondering about the invitation of Fay Weldon. Well, when I say wondering, I mean I was thinking, ‘Good choice’. For it was Fay Weldon, was it not, whose contribution to the Satanic Verses affair was:

‘The Koran is food for no-thought. It is not a poem on which a society can be safely or sensibly based. It gives weapons and strength to the thought-police — and the thought-police are easily set marching, and they frighten’ (Sacred Cows, 1989, p.6)

And when I say, ‘Good choice’, I really mean — well — on a discussion concerning the literary merits of the Qur’an versus the Old Testament, you could have invited a doctor of literature, an Old Testament scholar, one of the non-Muslim translators of the Qur’an. Rather than an author who is more associated with fictional tales of women trapped in oppressive scenarios. Though I admit, her contribution wasn’t lacking in that regard.

So a good choice if you’re stirring and you’d rather like to move beyond the ‘risk’ stage and onto to something more compelling. Effigies, bonfires, that kind of thing. Indeed, one blogger has already titled his post, ‘I smell a fatwa’ in anticipation. It would be a shame to disappoint.

But perhaps not the best choice if you seriously wanted to enlighten your listeners on the merits of one over the other. Never mind, we had Dr Mir. I can’t say I was awfully disappointed.

My dear editors — pardon me if I speak out of turn — but is it possible that you misjudged this one? Ever so slightly? I don’t even think Mr Faulks needs the publicity; his book seems to stand up on its own merits in the reviews I’ve read.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not averse to risk assessments (for I really must give you the benefit of doubt on this). No, I think they’re a jolly good thing. Indeed, I often think to myself, ‘If only I had done a risk assessment’ when another DIY job has gone terribly wrong.

No, it’s just that while undertaking your risk assessments, in order to have quantified the probability of Muslim anger properly, as well as identifying the hazard (Mr Faulks’ opinion) you really should have quantified exposure to the hazard, taking into account all of the environmental factors relevant to the case. Factors, I might posit, such as the fact that Muslims are currently fasting the month of Ramadan, which has numerous implications.

For example, it could be argued that a person who rises at 3.00am in the morning to take breakfast and then abstains from eating anything until just after 8.00pm might possibly feel somewhat weary, thus exhibiting less interest in manufactured schisms than usual.

Similarly it could be argued that a person who is spending their free time reading the Qur’an and standing the night in prayer, both ingrained habits of this month, may fail to get full exposure to said manufactured schism. Indeed, since many Muslims abstain from TV and internet use during this month, we are at risk of seeing the risk severely diminished.

Furthermore, you might possibly find that conditions of the fast such as restraining oneself from getting angry and holding one’s tongue from ill-considered speech lessens the likelihood of the full blown riot required. I could list other factors, but you’re intelligent folk; you get the gist.

Therefore, dear editors, I suggest you sit on this story for the time-being and then pull it out just as Parliament is debating the Religious Hatred Bill or something. Obviously you will have to think of another piece of legislation, as you used said Bill in 2006 when the issue of the Danish cartoons miraculously reappeared all across the media three months after the actual incident.

Not quite sure how you’ll bring it up again post-Ramadan; with the cartoon issue you had the redundancies at Arla foods. Perhaps when Mr Faulks gets nominated for the Booker Prize and you run the story, you could add this line: ‘Faulks courted controversy in August when he said…’ Well, you know the script already.

Risk assessments are all well and good. But sometimes there’s just no substitute for not publishing the story when you have a non-story. I know it’s us who look stupid when you run these stories, but the ultimate judge of stupidity lies elsewhere.

Kind regards,

etc. etc.

Every evening as Maghrib calls, a baby fox appears at our back door, ready to pounce… on a pair of slippers or a football. We have learned not to leave the garden flip-flops out now, for otherwise we will find them abandoned on the lawn in the morning, mildly chewed. So now the fox just stands there watching as we bow in prayer and then scarpers as we fall prostrate.

It is unsettling that I have a daily routine almost as regular as my five prayers: to peruse the online press for the latest reviews of the latest Netbook computers to go on sale. I am amazed by these little machines: attracted by their looks and fascinated by their form.

But just as the full force of this addiction kicked in, carrying me to Comet and Dixons to see numerous examples for real, a subtle realisation dawned… Actually, I have no need for a Netbook. I have an aging, second-hand laptop, which though far from perfect, serves my needs satisfactorily, and a desktop computer too. The truth is I’m suffering from technolust.

Over the years I have made myself deeply unpopular with acquaintances by voicing my fears of technolust aloud. Though undoubtedly irritating, every plea is heartfelt at the time. In a discussion on the merits of the iPhone vs the Blackberry, I will be found remonstrating that last year’s phone will suffice. My acquaintances respond in anger, demanding to know why I must inject irrelevant ideas into their discussions. Why don’t I just bog off, is the gist, though it is expressed with far more elegance.

Yet in truth I seek not to be a thorn in their sides. It is just that such discussions remind me of my own technolust. Yes, I really, really want a Netbook… but actually I have no need for one at all. It would just be a bit of a toy. Sure, we can all talk about the need to post our Twitter updates, to check our email and to post to our Blog wherever we are in the world. But actually that isn’t a need at all. It is a want and it is technolust. I’m sorry to say it, but it’s true.

I have always had this fear of gadgetry, or more specifically the cost of gadgetry. In my youth I was found yearning partly after a romantic past of subsistence farming and partly after a clean future harnessing the power of river currents. At university I studied environmental degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, seeking out low impact technologies to carry us forward.

And then I became a Muslim and learned that the best of our community lived lives that had minimal impact on the world around them. Some of the rulers of the early Muslim ummah shunned stallions to walk on the earth with humility. At night they slept like paupers. Their garments were unpretentious and their possessions few. Their lives mirrored the great sentiments of the gospels I had been raised upon.

And so what is the cost of our technolust? To the earth, the cost is great. To regional peace and stability, the cost is huge, fuelling mineral wars and civil strife all over. To our spiritual growth, only God surely knows. Our deen encourages restraint in terms of the food that passes our lips, the words that slip from our tongues, the gaze of our eyes and our craving for the delights of the world. For me, technolust is a modern extension of age-old trials. Yes, my injections into many a conversation are irritating, but they come from these thoughts. Ultimately the cause of my discomfort is my accountability before my Lord.

Nowadays such fears are quite inconvenient for I am paid to build websites and web applications, to keep abreast of the latest technologies and push boundaries. Websites — like this blog — depend on servers, and vast server farms exist to keep today’s internet running.

I believe I am a realist. Technology brings us great advantages, from CAT scanners and digital x-rays at the hospital to the washing machines and cookers in our homes, or from the video messaging allowing families scattered around the world to communicate face-to-face to the mobile phone enabling one to call for help in an emergency. Tis great and wondrous indeed.

But there is a line — I believe — somewhere here, but it is one that shifts constantly, blurring benefit, need and want. Many humans live comfortably without access to washing machines, but for those of us who have never known the world without them, such machines are considered a necessity. To speak with certainty about technolust is difficult in such shifting sands, but I believe we do retain a measure. It is our heart.

When the heart whispers that it is technolust, it probably is. When the heart whispers that we cannot justify spending all that money on yet another gadget, it is probably true. And when we look in our cupboards and see all of those other gadgets we thought we needed before, we can surely consider this a guide as well.

The cravings for the Netbook — or whatever the next gadget of the day would be — are certainly strong — but I am not going to fool myself with talk of some great need. I love shiny gadgets as much as the next man, but truth will always prevail. Though what I want is great, what I actually need is little; with the realisation that I suffer from technolust comes the recognition that somewhere in-between will suffice. Eat from the good things of the earth, yes, but do not go to extremes.