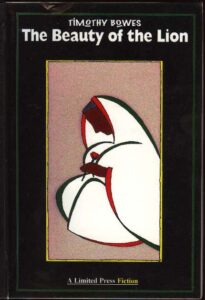

In 1996 I wrote a novel entitled The Beauty of the Lion. From a literary point of view, it was a disaster, but for me as the writer it was remarkably influential.

In 1996 I wrote a novel entitled The Beauty of the Lion. From a literary point of view, it was a disaster, but for me as the writer it was remarkably influential.

There was nothing remarkable about the book itself, except for its particularly sloppy style and poor punctuation. Indeed, I suppose the same story has been recounted a million times before, only with mildly different characters. This was no ground-breaking tale or spectacular innovation; it was, perhaps, just another tired-out rewriting of a quite ordinary life.

Yet as I occupied the lives of those characters for a few short months — mainly in the darkened hours — as I hammered the story into the keyboard and burnt my retinas with the word processor’s midnight glow, a whole new world opened up before me. It is quite true to say that this project started my writing habit, having avoided any kind of hard work throughout my schooling, but this is not what I have in mind. Rather, though completely unintended, my investment in those semi-imagined lives carried me along a path towards an unexpected destination.

The story accompanied two quite unlikely companions: a young Sikh woman from an irreligious family attempting to rediscover her faith and a young white man running away from his. But the story was not about religion, for these faiths were purely markers of identity. For the jumble of atheist, Sikh, Christian and Muslim characters race was the defining identity that caused tensions between them.

So a tale began of how two insecure characters could have become friends were it not for the intervention of their other acquaintances: the Pakistani Muslim girls who befriended the Sikh at school and warned her of the white boy’s crimes, and the boy’s Muslim friends who derided the girl for her odd ways. The Muslim characters were one dimensional, with few redeeming qualities. The girls were judgemental and racist, while the boys befell one misfortune after another.

Naturally, as these tales almost always go, eventually the two saw through the machinations of their advisers and decided to become friends. And so of course the Sikh girl’s brother threatened to break the white boy’s back, and her friends turned their backs on her, and a friendship was exaggerated into something akin to fornication, and though they denied that it was anything more, the girl finally faced the consequences of insinuation and was thrown out of the house and sent away.

And yet that was just the beginning. Fifteen chapters and a hundred thousand words later, a period of fifteen years having passed by in its pages, the novel ended on her son’s first day of school. Her job now ‘was to see that Benjamin-Piara, and Laila, would succeed the way she did, but without the heartbreak and the struggle.’ Apart from the terribly poor writing, it was quite a grim novel — the encounters with racists and criminals were hardly light entertainment — but it had a happy ending, of sorts.

For me, however, that was not the end of it. About four months after completing the project I moved down to London to begin a university degree. A few of my fellow students read copies of my novel, but they were all far too polite to offer any constructive criticism. It did not matter, for I had already come to terms with its flaws. Finding myself in a hugely cosmopolitan environment, interacting with people from all sorts of backgrounds, I was suddenly conscious of the one dimensional nature of the characters in the book and the great complexities of real people. Gradually I was becoming sympathetic to some of the antagonists in my novel and more critical of the two main characters.

As the year wore on and I honed my writing skills penning essays on environmental degradation and theories of economic development, I knew that I had to rewrite that novel. At first I just wanted to improve the quality of the writing, which I knew was poor and immature, but as I committed to revisiting the story it began taking on a life of its own.

The Sikh girl’s friends were not as bad as I had thought. One was just principled in her beliefs. She had her faults like anyone, but her objections to the boy came not from malice, but out of genuine concern for her friend. The Sikh girl was not as certain about beliefs as I had thought: she was just putting out feelers, stumbling to find her way in an environment devoid of guidance. The boy was no pure victim of the vindictiveness of others: he had played an active role in messing up his life.

By the time I returned to my word processor at the start of the summer break and began the novel anew, it was already a different book. Where it had once been clearly about race, now it was threaded with ambivalent questions of faith. Where there was once a certainty about the rightness of some characters and wrongness of others, there was now uncertainty in everyone. The girl that was the thorn in the side of the main players in the first draft had somehow won my respect.

By the time I returned to my word processor at the start of the summer break and began the novel anew, it was already a different book. Where it had once been clearly about race, now it was threaded with ambivalent questions of faith. Where there was once a certainty about the rightness of some characters and wrongness of others, there was now uncertainty in everyone. The girl that was the thorn in the side of the main players in the first draft had somehow won my respect.

In the process of writing a piece of fiction, it was as if the writer had moved a thousand miles. My summer break proved too short and by my return to university to begin my second year of studies I had only completed half of the rewrite, and that was as far as I ever got. My writing had carried me — though not alone, for there were other influences too — towards another world. Before the following summer I would be a treading a new path myself. Not as a well defined, one dimensional creature, but a complicated, ambivalent character that a far greater Creator had willed into existence.

I shall forever be grateful for the pen, for bringing me this far from home. And to the publisher who recognised that the manuscript was best consigned to the bin.

Last modified: 21 September 2024

Very interesting read. I think it is inevitable that an old work appears different (not necessarily inferior) to what can be produced currently because writing stems from experience, so as we mature we look a little deeper. And I thought the story was quite good actually and would work for a TV series.

I had forgotten you had seen it.